Roger Guenveur Smith Tackles Rodney King

Kirk Douglas Theatre, Culver City – LA

9/18-10/6 2013

words/photos by: Ani Yapundzhyan

Roger Guenveur Smith has spent a career going after intense characters-complex personalities that perhaps ease his own complexities. In theatre and on film he portrayed Huey P. Newton-capturing Newton’s nuances, quirks and neuroticism in chillingly accurate form. His other credits include plays on Jean-Michel Basquiat and Frederick Douglass, among others.

This week, I saw him tackle Rodney King– and more accurately, the fears, attitudes and feelings of the world as they understood Rodney King.

With the sound of a police radio preceding “Can’t we all get along?” on loop, Smith steps on the small stage and begins his one-man monologue with a powerful quote from Geto Boys’ Willie D:

“Fuck Rodney King in his ass

When I see the motherfucka, I’mma blast

Boom in his head, boom, boom, in his back, just like that…”

The actual song itself sounds like a Public Enemy-style track-the beat, the intense rhythm, the style of rap. But Smith is vocalizing it theatrically. The words are clear, loud, and hit home.

A couple of people walk in late and take their seats in the front row, Smith stares at them and improvises, “Fuck y’all, too.”

Afterward, in a discussion proceeding the monologue, an older white lady in the crowd will say that she was repulsed by the hostility of those words yet attracted to them at the same time.

“Thank you for your repulsion,” Smith will respond.

Back to the monologue that transports Smith through the many layers of Rodney Glen King’s persona.

A major, ironic point that surfaces again and again is King’s love of the water-Rodney-“Glen” as he was known as a youngster-had an affection for the water-his father taught him how to swim up above the Altadena reservoir. His father, whom King found drowned in a bathtub, taught him how to swim in an Altadena reservoir.

Smith weaves in and out of the seemingly conflicting parts of King’s existence.

He touched on King’s prior criminal history before the LAPD beating. Referring to a 1989 convenience store robbery in which King knocked over a pie rack, he says, “Assault with a deadly apple pie, you know that’s an All-American offense.”

As he begins to speak of the night of King’s beating, he mentions what King and his two friends were listening to as they drove around that night: “NWA, that would be cliche. You were playing De La Soul, from the soul.”

“They said that you lose more blood than any man had ever lost and lived on.”

In a Gil-Scott Heron, “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised”-eque manner, Smith exclaims:

“Your’e spitting blood like that great white whale in that great white novel by that great white novelist.”

11 skull fractures.

Then he speaks the obvious truth:

“You went viral before viral was viral…before you know it, Rodney King, you’re the first reality star.”

Focusing on the social implications that went beyond the actual beating, the events afterward that fucked up the entire country, he goes down the list of the victims of the LA Riots that followed:

-15 year old Latasha Harlins, who was shot in the head by a Korean liquor store owner while attempting to buy orange juice.

-Edward Song Lee, 18, who was mistaken for a looter and shot and killed by other Korean-Americans.

-A 68-year old man who was strangled to death.

“Rodrigo Rivas, such a beautiful Shakespearean name. Rodrigo Rivas, shot down by the national guard.”

“John Doe #50, burned to a crisp in the back of a Pep Boys. They don’t know if his name was Manny, Moe or Jack.”

After poignantly telling the stories of these victims of murder during the riots, Smith says,

“Let it go, Glen…let it go…”

Is he speaking of the guilt that King probably carried with him in the aftermath and after so many people lost their lives?

Two dates are inscribed along the pool wall in which King drowned: 3/3/91, the day King was beaten, and 4/29/92, the day a jury acquitted three of the four officers who beat him.

“Let it go, Glen…let it go…”

In the discussion following his monologue, Smith says to the audience: “This is not so much a performance as it is a prayer. Thanks, Rodney King for providing the scripture….and there’s things that he meant to say that he never got to say, things that he wanted to say that he couldn’t get to, his brain wouldn’t make the connect, but his heart was there. And isn’t it ironic that he had an abnormally enlarged heart? And he shared it with us.”

At his death, King’s heart weighed 480 grams, normal person of his stature’s heart weight is 360 grams.

“I think that Rodney King’s speech on May Day 1992 was one of the great American speeches. It’s right up there with the other King…I think that what he left us was a fundamental guide for survival…what a magnanimous statement coming from a man who had the shit beat out of him.”

Rodney King was born in 1965, same year that Malcolm X died, same year as the Watts Riots, and year that Bill Cosby became the first black man to win an Emmy.

King died on “Father’s Day night”

“I knew that he had an affinity for water,” Smith continues in the discussion, “there was a cover story on him in the LA Times Magazine some years ago, that was a beautiful picture of him with a surfboard on the beach, and it was all about him surfing. and I knew that his father taught him how to swim, I didn’t know that he skied, he was a skier, but yes, to have met his fate in tragically the same way that his father met his fate as well, his father drowned in a bathtub, and he found him. And he drowned in a swimming pool, on Father’s Day.

It’s a tremendously tragic circumstance. I hope that there’s a lesson there somewhere, I don’t know what that lesson might be, but I know that again, he’s left us with a tremendous legacy of Wisdom and I also think that the beating that began on March 3rd, 1991, was not complete until Father’s Day 2012, that was the final blow. It may have been self-inflicted, but it was part of the same process.”

Ronald King, Rodney’s father, drank himself to death in a bathtub at the family home. Rodney struggled with alcohol his whole life, most of his troubles with the law stemming from it.

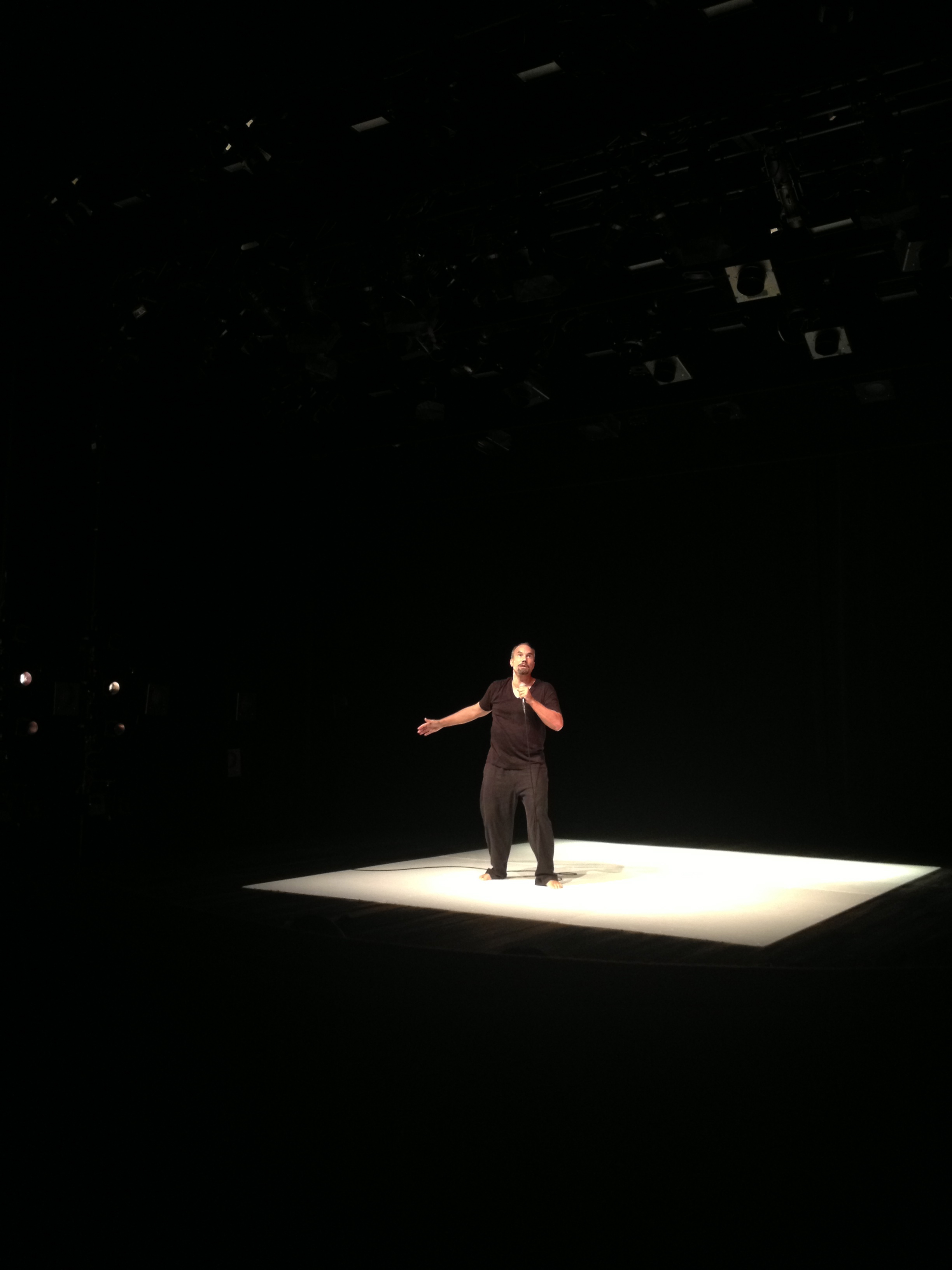

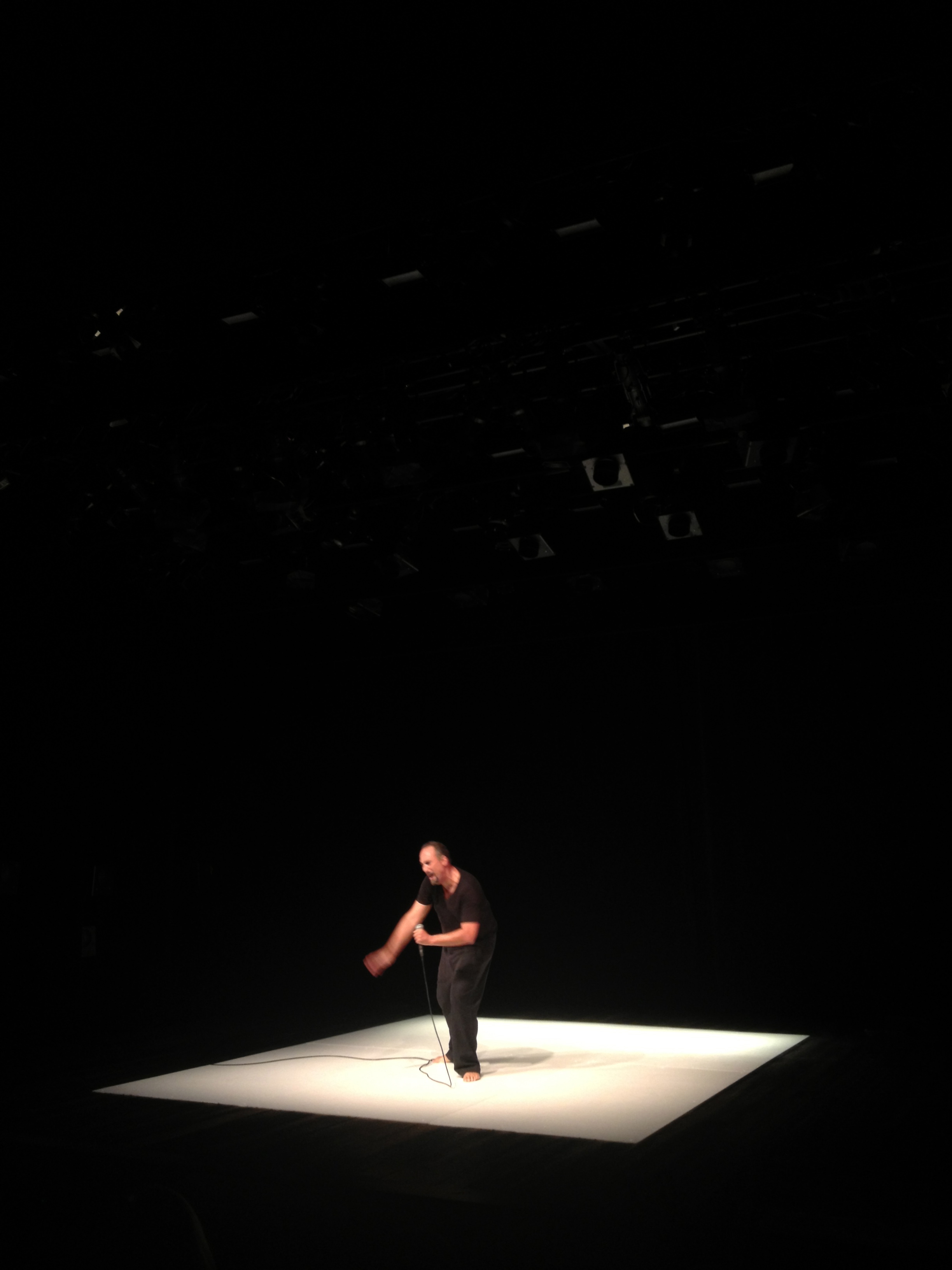

Roger Smith finishes his monologue with movements that are as powerful as the words he has now ceased to speak:

He is standing in silence on a white mat. He begins making surfing motions, a smile on his face, as if riding the waves. After a few moments, he is drowning, his face becoming scared and haggard.

As he takes his leave, Kendrick Lamar‘s “Swimming Pools” booms from the speakers:

“Pour up (drank, drank), head shot (drank, drank)

Sit down (drank, drank), stand up (drank, drank)

Pass out (drank, drank), wake up (drank, drank)

Faded (drank, drank), faded (drank, drank)

Now I done grew up

Round some people living their life in bottles

Granddaddy had the golden flask

Back stroke every day in Chicago…

I got a swimming pool full of liquor and they dive in it

Pool full of liquor I’ma dive in it”

As I walked back to my car after the show, shook, I felt it appropriate to put my Gil-Scott playlist on shuffle.

What do you suppose was the first song that came on?

“The bottle.”

“See that black boy over there runnin’ scared

His old man in a bottle

He done quit his 9 to 5

He drink full time and now he’s livin’ in a bottle.”

Rodney King loved the water. He felt alive in the water and lost his life in the water. The drowning in his swimming pool was maybe his final release from a lifetime of drowning in a bottle.